“I can’t do it, dad.”

“Why do you say that?”

“You see. I keep trying and I haven’t made it once.”

Iakovos P. and his six and a half year old daughter, Theodora, are at the playground, where she has been trying to climb up the slide the wrong way for about half an hour. He looks at her furrowed brow, at how frustrated this is making her.

“Theodora, if you continue, you always have a chance. Only quitting is final.”

This pep talk is enough, as it often is, he says, to get her to keep at it; sure enough, on her seventeenth try, she succeeds.

Theodora is not your stereotypical little girl with ponytails and a pretty dress. “She’s always been something of a tomboy,” he tells me. “She’s already the tallest girl in her class and can outrun all of them. As her interests are mostly athletic, I’ve already taught her how to swim, ride a bike and ski—-which she’s faster at than her mother now, I might add. She finds princesses boring and has never understood why anyone would want to be one. When I asked her what she’d rather be instead, she asked if there were any girl warriors to emulate. I told her about Joan of Arc and Boudica, but

most importantly, I explained that gender doesn’t define your ability to do anything, including be a princess or a warrior. You should be whatever you want to be regardless.

Iakovos does a lot of mindset work and motivation work with his daughter, in general, to help her understand concepts like this, and things like the difference between good and bad choices, the importance of being honest, and how, right or wrong, to be able to accept responsibility for your actions. Rather than pose any of it theoretically, he uses the every day situations they find themselves in to illustrate these examples, such as when they’re running late for somewhere they need to be; instead of ever pinning it on any individual entirely, he explains how they might share it as a team. “The most rewarding part of being a father is teaching her these things, ownership for her part in any situation, how to stand up for her values and never quit just because something is hard to do.”

Seeing what I teach her become part of her life and realizing that’s me becoming more of a part of her life is incredible.

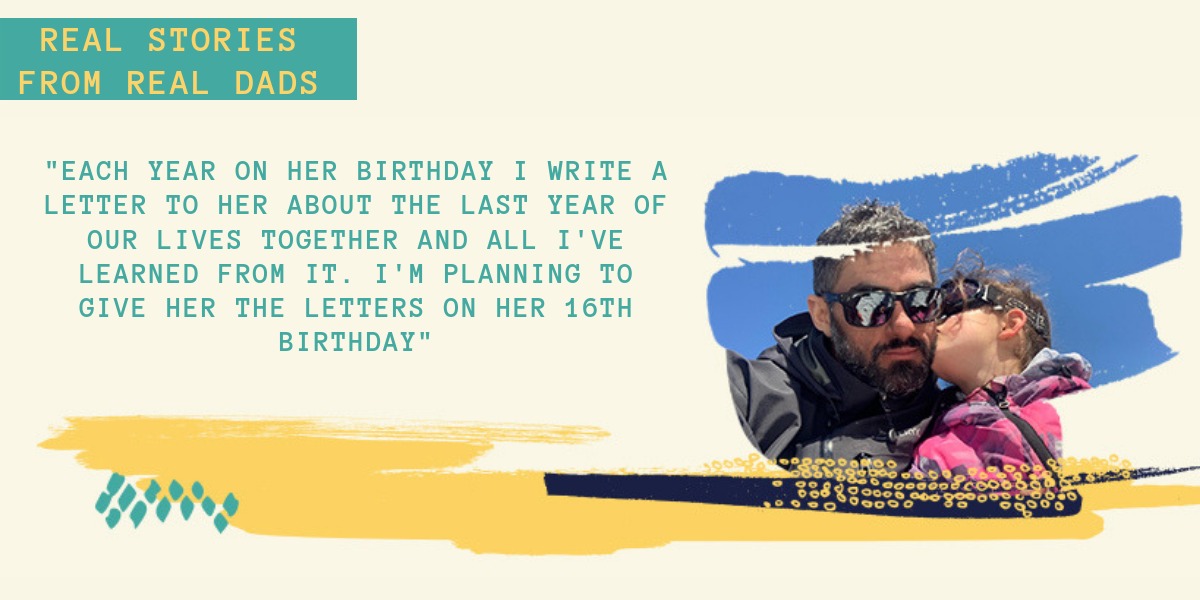

Each year, on her birthday, Iakovos sits down and writes a letter to her about the last year of their lives together and all he’s learned from it. “Most of it is related to her, things we’ve done together,” he says. “But not all of it. Some of what I share are about personal experiences, how I felt while going through them and why.”

I want her to understand more about my inner world through this abbreviation of her life from the time she entered into it.

Iakovos plans to give them to her on her sixteenth birthday and says he looks forward to the conversations he hopes they’ll have from memories he touches on in there, things she may want to know more about. “Nothing gets by her, even now,” he tells me. “She’s very emotionally intuitive, but often I realize she’s too young for me to explain in detail everything I’d like to tell her. So I note it down and put it in the letter so that one day, when she has them all in her hands, if she still wants to know more, we’ll be able to do it then.”